Convention No. 190 refers to violence and harassment as a single composite concept covering “a range of unacceptable behaviours, practices or threats thereof”, rather than providing a closed or uniform definition of what constitutes violence and/or harassment in the world of work.

Definitions

Article 1

- For the purpose of this Convention:

- the term “violence and harassment” in the world of work refers to a range of unacceptable behaviours and practices, or threats thereof, whether a single occurrence or repeated, that aim at, result in, or are likely to result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm, and includes gender-based violence and harassment;

- the term “gender-based violence and harassment” means violence and harassment directed at persons because of their sex or gender, or affecting persons of a particular sex or gender disproportionately, and includes sexual harassment.

- Without prejudice to subparagraphs (a) and (b) of paragraph 1 of this Article, definitions in national laws and regulations may provide for a single concept or separate concepts.

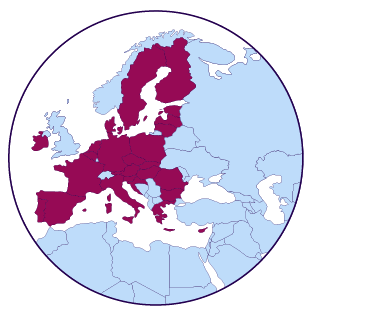

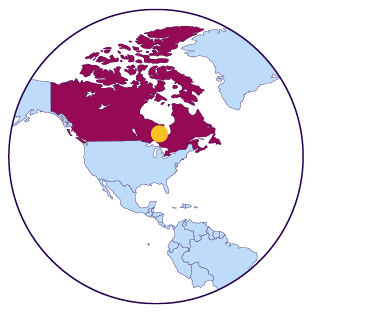

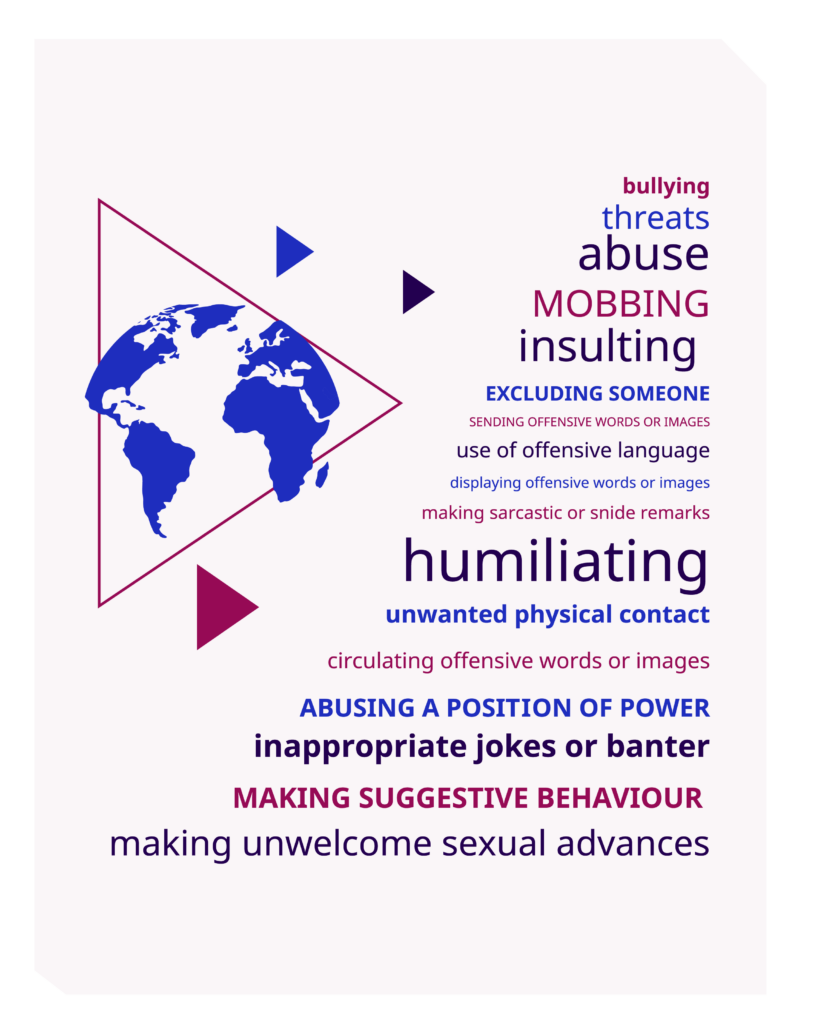

This approach allows for the flexibility needed to cover various manifestations of violence and harassment, including new ones that emerge over time (ILO 2018b). It also allows for “violence and harassment” to cover a wide range of terms found in different legislation to describe the same or similar phenomena (see figure 2). These laws often acknowledge that there is no clear line between violence and harassment (ILO 2018b; 2019b).

The definition in Article 1(a) is comprised of two elements. The first is the prohibited conduct, which encompasses “a range of unacceptable behaviours and practices, or threats thereof”. The use of the term “range” clarifies that violence and harassment can be understood to encompass conduct of different natures, which can be either independent behaviours or a combination of behaviours, including escalating ones (ILO 2018b). Whether a single occurrence may be sufficient to be considered violence and harassment, or whether it must be repeated conduct, in all cases such conduct must be “unacceptable”, based on subjective and objective considerations (ILO 2019b). To be unacceptable, this

conduct should “aim at, be likely to result or result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm”. The inclusion of “economic harm” along with physical, psychological and sexual harm ensures that all forms of violence and harassment are encompassed. Economic harm could consist of loss of income or property damages, but also restrictions in accessing financial resources, education or the labour market, including restricting a person’s ability to remain in or advance in the labour market.

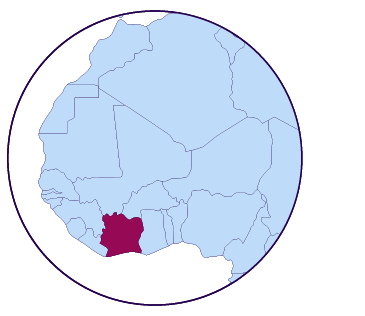

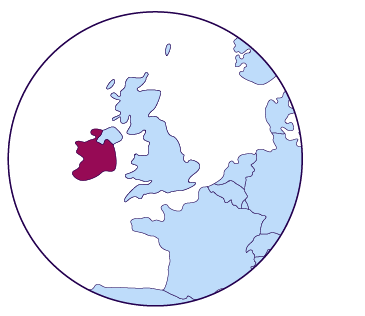

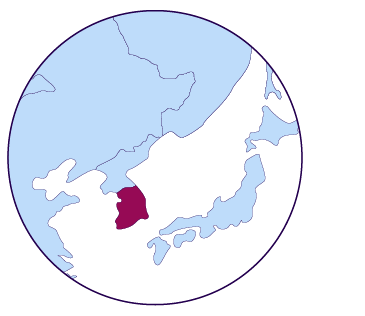

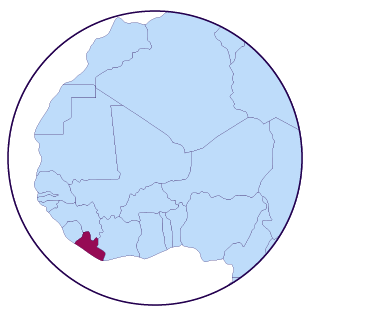

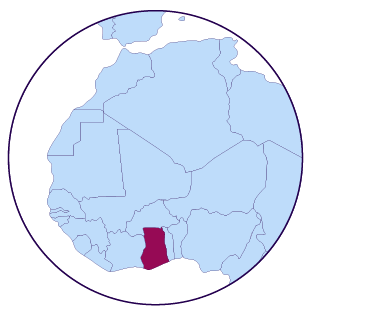

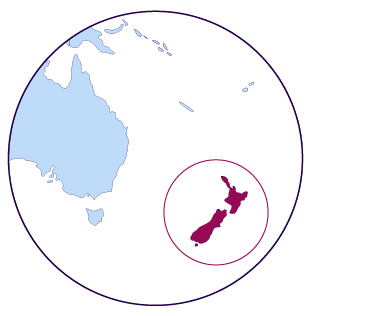

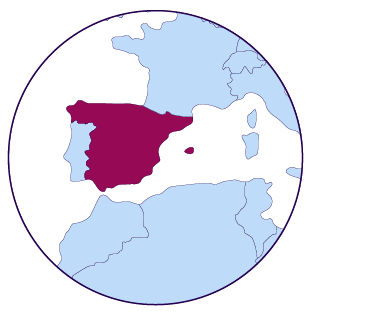

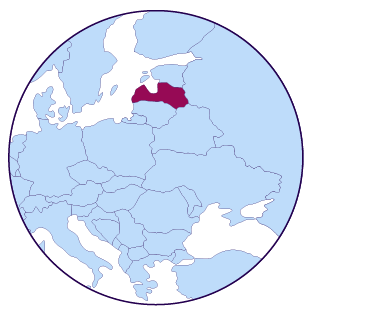

Figure 2. Violence and harassment in the world of work: A broad range of terms

The definition does not include the intent as one of the constitutive elements.6 By not including intent, Convention No. 190 adopts a pragmatic and victim-centred approach, which focuses on the unacceptability of the conduct, practices or threats, and on their effect on victims. The absence of any reference to perpetrators in the actual text of Article 1 reinforces the purpose of the instruments, which is to prohibit all forms of violence and harassment in the world of work, regardless of their source, whether it be:

- by or against individuals exercising the authorities, duties or responsibilities of an employer (vertical)

- directed toward one’s peers (horizontal), or

- involving third parties, such as clients, patients, passengers or customers.

While Convention No. 190 proposes a single concept covering violence and harassment, it takes into account the diversity of national legal systems and regulatory approaches, and allows States to opt for a single concept or separate concepts in their definitions in national laws and regulations (Art. 1(2)), while ensuring that all the elements of the definition provided by Convention No. 190 are respected (ILO 2019e; 2019b). This provision relates directly to the obligation stemming from the Convention to “define and prohibit violence and harassment in the world of work” (Art. 7). This is essential, as legislation lays the foundation for a culture of respect, including at work, and can trigger lasting change in society. By promoting a culture of dignity and respect for all, the law plays a crucial role in the prevention and eradication of violence and harassment. It can guide the development of prevention programmes, promote accurate identification of causes and consequences, ensure investigation, and provide protection and support for complainants, among other things.

Box 1. Examples of definitions of violence and harassment in recent legislative reforms

2.1.1. Gender-based violence and harassment

The notion of violence and harassment outlined in Article 1(a) of the Convention, explicitly includes “gender-based violence and harassment”. By embedding it in the overarching definition of violence and harassment, the elements of the offending conduct and the resulting or aimed impact are also applicable to the concept of gender-based violence and harassment (ILO 2018b, para. 273).7

For further clarity, the Convention defines gender-based violence and harassment as “violence and harassment directed at persons because of their sex or gender, or affecting persons of a particular sex or gender disproportionately, and includes sexual harassment” (Art. 1(b)):

- The reference to “persons” is significant, as it broadens the definition of gender-based violence compared to other international and regional instruments. While gender-based violence and harassment disproportionately affects women and girls – as the Preamble of Convention No. 190 recognizes – Convention No. 190 seeks to protect everyone from such behaviours. 8

- The reference to “sex or gender” makes both the biological functions and characteristics that differentiate men from women (that is, sex) and the sociological differences between men and women that are learned and changeable over time (that is, gender) relevant to Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 (ILO 2012).

The definition of gender-based violence and harassment explicitly includes “sexual harassment”. As a serious manifestation of sex discrimination and a violation of human rights, sexual harassment has been addressed prior to the adoption of Convention No. 190 within the context of the ILO Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111) (ILO 2012; 2020a; Cruz and Klinger 2011; ILO and UN Women 2019). Within that framework, and according to the 2002 General Observation of the ILO CEACR, definitions of sexual harassment contain the following two key elements:

- Quid pro quo – Any physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature and other conduct based on sex affecting the dignity of women and men, which is unwelcome, unreasonable, and offensive to the recipient; and a person’s rejection of, or submission to, such conduct is used explicitly or implicitly as a basis for a decision which affects that person’s job; or

- Hostile work environment – Conduct that creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating working environment for the recipient.

Box 2. Advancing protection against gender-based violence and harassment in work-related legislation

In recent years, many countries have introduced specific provisions in work-related legislations aimed at defining gender-based violence and harassment and, in particular, sexual harassment.

Convention No. 190 acknowledges that to be able to fully prevent and eradicate gender-based violence and harassment in the world of work, ratifying countries must address its root causes, such as multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination; unequal gender-based power relations; gender stereotypes; and gender, social and cultural norms that support violence and harassment. With a view to tackling the root causes of gender-based violence and harassment, as well as to reducing their harmful effects, Convention No. 190 calls for the adoption of a “gender-responsive approach”. Gender-responsiveness means intentionally employing gender considerations to affect the design, development, implementation and results of programmes and strategies, policies, laws and regulations, as well as collective agreements. This implies an approach that: reflects all girls’ and women’s realities; pays attention to their unique needs; ensures their participation in decision-making processes at all levels; values their perspectives; respects their experiences; and understands the developmental differences between girls and boys, women and men in all their diversity and throughout their life cycle. The ultimate aim is to empower girls and women, with a view to promoting gender equality in practice and achieving gender equity.

Domestic violence and the world of work

Historically, domestic violence has been relegated as a “private” issue, with no connection to the public sphere or to the world of work. Significantly, Convention No. 190 recognizes the negative spillover effects that domestic violence can have in general on the world of work, including in relation to employment, productivity, and safety and health. The Convention also recognizes the positive contribution that governments, employers’ and workers’ organizations, and labour market institutions can play in mitigating the impact of domestic violence on the world of work (Preamble and Art. 10(f)). Domestic violence can represent a particular risk that impairs the health and productivity of all workers and other persons concerned, including individuals exercising the authority, duties or responsibilities of an employer (ILO 2020b; 2020c). Some work-related places, situations or instances – particularly those which are easily accessible by the public, such as schools, hospitals, public services or street markets, among others – can be places where domestic violence is unleashed. Likewise, domestic violence represents an even more relevant risk for particular work arrangements, such as working from home, as well as for some categories of workers, such as domestic, home-based or contributing family workers, many of whom are women working informally (ILO 2021c).

Preamble

Noting that domestic violence can affect employment, productivity and health and safety, and that governments, employers’ and workers’ organizations and labour market institutions can help, as part of other measures, to recognize, respond to and address the impacts of domestic violence, and

Article 10

Each Member shall take appropriate measures to: …

(f) recognize the effects of domestic violence and, so far as is reasonably practicable, mitigate its impact in the world of work.

Following on from these provisions in the Convention, Paragraph 18 of Recommendation No. 206 sets out a number of measures that could be adopted to respond to and mitigate the impacts of domestic violence, such as:

- leave for victims of domestic violence;

- flexible work arrangements and protection for victims of domestic violence;

- temporary protection against dismissal for victims of domestic violence, as appropriate, except on grounds unrelated to domestic violence and its consequences;

- the inclusion of domestic violence in workplace risk assessments;

- a referral system to public mitigation measures for domestic violence, where they exist; and

- awareness raising about the effects of domestic violence.

Box 3. Examples of labour and employment provisions acknowledging the effects of domestic violence in the world of work and mitigating its impact

In recent years, countries have increasingly taken into account the effects of domestic violence on workers’ well-being and productivity in their labour and employment provisions. A growing number of countries have introduced leave, whether paid or unpaid, for workers who are victims of domestic violence. Others have included domestic violence as a ground of discrimination in employment and occupation, and require employers to provide reasonable accommodations. Some have envisaged employers’ duties to take preventive measures to protect the employee or other workers, or included domestic violence within the management of occupational safety and health (OSH). In addition, with a view to protecting specific categories of workers, such as domestic workers, against violence and harassment, some laws and regulations have extended the definition of “domestic violence” beyond traditionally understood family relationships to include those working in the domestic sphere.

Box 4. Examples of collective agreements and other measures addressing domestic violence in the world of work

Social partners have also been very active. In several countries, collective agreements and other measures have been taken in relation to domestic violence, including training, provisions of flexible working arrangements, paid leave and support services.

6 In this regard, it is worth mentioning that within the framework of the ILO Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111), the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR) has already pointed out that the lack of intent or the existence of intent should not be relevant in harassment issues ; see ILO 2012.

7 During the standard setting process, it was clear that the term “gender-based violence” included both hostile working environment and quid pro quo sexual harassment. However, for consistency with the concept of violence and harassment as a range, and in light of the recent outcry and public debates related to the #MeToo campaign, which have highlighted the significance of sexual harassment, including in the workplace, it was agreed to add a clear reference to sexual harassment, while cognizant of the fact that gender-based violence does include sexual harassment.

8 See Carlson and Olney, forthcoming.

9 Many Canadian provinces/territories are also moving in this direction. See, for instance, Yukon Territory, where section 19.05 of the 2020 Occupational Safety and Health Regulations provides that “if an employer becomes aware, or ought reasonably to be aware, that a worker is or is likely to be exposed to domestic violence in the workplace, the employer must take reasonable precautions to protect the worker and any other persons in the workplace who are likely to be affected”.

10 As an example, see the Australian Jewish News Journalists Enterprise Agreement 2019 (Australia 2019). Since August 2018, family and domestic violence leave provisions have been inserted into all 122 of Australia’s modern awards, with a model clause developed for inclusion (Australia 2018).