Article 10 of Convention No. 190 includes a number of measures based on existing practice at the national level that each country could implement or strengthen based on national circumstances. To proactively enable and encourage reporting of violence and harassment, and to effectively respond to such complaints, Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 state principles that should be ensured irrespective of the concrete procedure enacted at the national or workplace level, as explained below.

6.1.1. Ensuring easy access, safety, fairness and effectiveness

Complaint mechanisms can be either internal (within an enterprise) or external (through the Ministry of Labour or other relevant ministries, court systems, sectoral or collective mechanisms, specialized tribunals or courts, labour inspectorates, dispute resolution agencies, human rights and equality bodies, or other quasi-judicial bodies).

Regardless of the specific mechanism, Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 state that all these channels should be easily accessible, safe, fair and effective. <sup>33</sup>

Internal complaint mechanisms are often foreseen by labour legislation, including OSH regulations, and by collective agreements, and may require the complaint to be taken by the supervisor, or where the supervisor is the alleged perpetrator, by another person.

Box 24. Ensuring access to justice at the workplace level

Recently, steps have been taken in several countries to include specific procedures in case of violence and harassment, including by setting up dedicated internal committees or by providing anonymous reporting.

Conciliation, mediation and arbitration may also be available or required when a complaint is lodged either internally (through dispute resolution or grievance procedures under collective agreements) or externally (through in-court conciliation, extrajudicial conciliation through autonomous procedures, or by public administration systems). Practice has shown that different approaches focusing more on generating an attentive and responsive dialogue by hearing both parties’ voices, seem to overcome the adversarial nature of legalistic models, increase complainant satisfaction, and reduce retaliation (Dobbin and Kalev 2020).

Box 25. Violence and harassment and non-disclosure agreements

In some jurisdictions, an increasing number of provisions aim at overcoming the practice to include disputes related to violence and harassment – and in particular gender-based violence and harassment and discrimination – within the scope of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). These NDAs typically include, among other things, confidentiality and mutual non-disparagement provisions, which prevent the parties from discussing the terms of the settlement as well as the circumstances surrounding the settlement. Following several high-profile scandals, some countries have taken measures to make sure that NDAs are not used to silence victims or whistle-blowers, irrespective of their contractual status, who allege any misconduct, particularly sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination-based harassment. In this regard, Article 10(c) of Convention No. 190 states that ratifying States should “ensure that requirements for privacy and confidentiality are not misused” (ILO 2019c, para. 828).

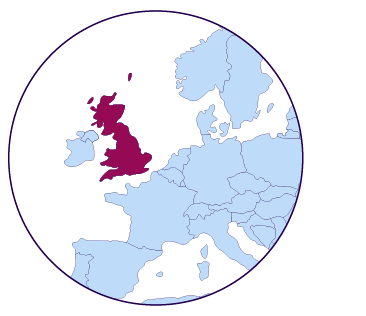

For instance, in 2020, the United Kingdom’s arbitration service Acas has advised firms and workers against using NDAs to prevent someone from reporting sexual harassment, discrimination or whistle blowing at work (Acas 2020). In the United States, provisions have been introduced in many states to prevent the misuse of NDAs. For instance, in New Jersey, employers can no longer enforce NDAs relating to discrimination, harassment and retaliation claims against current or former employees under a law that became effective in March 2019 (Avallone and Meade 2019).

In the same year, New York State adopted regulations stating that a worker cannot be bound by any agreement signed after 11 October 2019 that prohibits the worker from disclosing harassment facts or settlement of a claim of harassment on any protected category basis unless that is the worker’s preference. 35

In recent years, many countries have embarked on legislative reforms to ensure that external complaint mechanisms for cases of violence and harassment in the world of work are safe, easy to access and provide timely processing, particularly in cases involving discrimination-based behaviours.

Box 26. Strengthening reporting and dispute resolution mechanisms external to the workplace

In relation to gender-based violence and harassment, Convention No. 190 provides that complaint and dispute resolution mechanisms should be “gender-responsive” (Art. 10(e)). This includes, for instance, designing and ensuring that judicial and non-judicial mechanisms are responsive to the barriers faced by victims of gender-based violence and harassment in seeking effective remedies and in reducing the harmful effects of such prohibited behaviours. Recommendation No. 206 offers further guidance, by recommending that courts be equipped with the necessary expertise and legal advice (Para. 16(a)-(c)); that assistance for complainants and victims, as well as guides and other information resources be provided (Para. 16(c)–(d)); and that the burden of proof be shifted, as appropriate, in proceedings other than criminal ones (Para. 16(e)).

Box 27. Gender-responsive reporting and dispute resolution mechanisms: Some examples

6.1.2. Protection before, during and after reporting or making a complaint

Convention No. 190 recognizes the right of workers to remove themselves from a work situation which they have reasonable justification to believe presents an imminent and serious danger to life, health or safety due to violence and harassment. Additionally, workers should be able to exercise this right without suffering retaliation or other undue consequences, while having a duty to inform their employers (Art. 10(g)). 36 This protection is found in relevant OSH standards. In particular, Article 13 of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155), which states, “A worker who has removed himself from a work situation which he has reasonable justification to believe presents an imminent and serious danger to his life or health shall be protected from undue consequences in accordance with national conditions and practice.”

Throughout the reporting, investigation and dispute resolution process, Convention No. 190 calls for the protection of privacy and confidentiality, to the extent possible and as appropriate (Art. 10(c)). The confidentiality of complaints is essential to protecting the privacy of both the complainant and the alleged perpetrator. However, privacy and confidentiality should not impede an investigation. Related to this, ratifying States are also to “ensure that requirements for privacy and confidentiality are not misused” (Art. 10(c)).

Box 28. Ensuring privacy and confidentiality, and the right to remove oneself from a harmful situation

Convention No. 190 also protects against any forms of victimization or retaliation against complainants, victims, witnesses and whistle-blowers (Art. 10(b)(iv)). Protecting complainants from retaliatory actions is a fundamental part of safe and effective reporting, complaint procedures and dispute resolution mechanisms.

Box 29. Protecting against victimization and retaliation

6.1.3. Support services

Among the possible measures to enable effective reporting and dispute resolution mechanisms and procedures, Convention No. 190 mentions “legal, social, medical and administrative support measures to complainants and victims” (Art. 10(b)(v)). Support services should be gender-responsive, particularly in case of gender-based violence and harassment (Art. 10(e)). In this regard, Recommendation No. 206 recommends:

The support, services and remedies for victims of gender-based violence and harassment referred to in Article 10(e) of the Convention should include measures such as:

- support to help victims re-enter the labour market;

- counselling and information services, in an accessible manner as appropriate;

- 24-hour hotlines;

- emergency services;

- medical care and treatment and psychological support;

- crisis centres, including shelters; and

- specialized police units or specially trained officers to support victims (Para. 17).

Box 30. Examples of legislation and regulations providing protection and support to victims

6.1.4. Appropriate and effective remedies

Article 10 of Convention No. 190 requires ratifying States to ensure appropriate and effective remedies. In this regard, Recommendation No. 206 recommends that remedies could include:

- the right to resign with compensation;

- reinstatement;

- appropriate compensation for damages;

- orders requiring measures with immediate executory force to be taken to ensure that certain conduct is stopped or that policies or practices are changed; and

- legal fees and costs according to national law and practice (Para. 14).

By requiring appropriate and effective remedies, Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 call for effective enforcement of legal rights and redress, which, when appropriate and possible, could provide restitution and relief to the person whose rights have been infringed, and could have a dissuasive effect on potential perpetrators. These effective remedies depend on a variety of factors, including the severity of the conduct and the legal pathways chosen by the plaintiff in each legal system. The explicit reference to “reinstatement” as well as to “orders requiring … that certain conduct is stopped or that policies or practices are changed” highlights that, in case of violence and harassment, monetary damages may be inadequate to fix the harm. 37

Within the context of the effective remedies provided for by Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206, the importance of employment injury benefits for victims of violence and harassment at work is also recognized. In particular, Recommendation No. 206 recommends that “victims of violence and harassment in the world of work should have access to compensation in cases of psychosocial, physical or any other injury or illness which results in incapacity to work” (Para. 15). Physical injury and some mental disorders are compensable injuries under employment injury insurance and workers’ compensation schemes if the event triggering the injury or illness arises out of and/or in the course of employment. Such schemes ensure access to necessary medical care as well as counselling, rehabilitation and reintegration for affected workers. These schemes also provide cash benefits to victims and their families (in case of death), which prevent them from falling into poverty and social exclusion due to loss of income, loss of earning capacity and income support, as the case may be (Chappell and Di Martino 2006; Lippel 2016; ILO 2018g).

Box 31. Remedies in case of violence and harassment at work: Recent exeples

6.1.5. Sanctions

Article 10(d) of Convention No. 190 states that ratifying countries should “provide for sanctions, where appropriate, in cases of violence and harassment in the world of work”. Sanctions refer to consequences for ill-behaviour, and their nature depend on the circumstances, on the behaviour being punished, and on the specific jurisdiction in which the complaint or claim is lodged or the legal pathway chosen. Sanctions may therefore refer to both disciplinary measures, and other civil, administrative or criminal sanctions, where appropriate. Recommendation No. 206 further specifies, “Perpetrators of violence and harassment in the world of work should be held accountable and provided counselling or other measures, where appropriate, with a view to preventing the reoccurrence of violence and harassment, and facilitating their reintegration into work, where appropriate” (Para. 19).

Box 32. Sanctions in case of violence and harassment at work: Recent examples

33 As a group of experts who contributed to the development of the ILO Examination of Grievances Recommendation, 1967 (No. 130) argued, “Fair and effective procedures … which provide for an orderly outlet for grievances constitute a safety-valve which helps to prevent the outburst of serious disputes. Moreover, such procedures can contribute to a climate of mutual confidence between management and workers which is so necessary in labour-management relations” (ILO 1964, para. 39). Although, to date no single ILO instrument provides broad and comprehensive guiding principles for effective labour dispute resolution systems, some guidance and principles concerning individual labour disputes are spread throughout various instruments, including the ILO Voluntary Conciliation and Arbitration Recommendation, 1951 (No. 92), and the ILO Examination of Grievances Recommendation, 1967 (No. 130). More recently, the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169), provides that the peoples concerned “shall be safeguarded against the abuse of their rights and shall be able to take legal proceedings, either individually or through their representative bodies, for the effective protection of these rights” (Art. 12). The Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189), mandates to “take measures to ensure … that all domestic workers, either by themselves or through a representative, have effective access to courts, tribunals or other dispute resolution mechanisms under conditions that are not less favourable than those available to workers generally” (Art. 16). Ensuring “effective access to justice” is also one of the policies recommended by the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204). In general, and for a comparative analysis on this topic, see Ebisui, Cooney, and Fenwick 2016; ILO 2018f, ILO 2013.

34 Supreme Decree N° 014-2019-MIMP

35 If it is the worker’s preference, then a three-step process must be followed: 1. the nondisclosure term must be written in an agreement in plain English and, if applicable, the worker’s primary language as well; 2. the worker must be given at least 21 days to consider the non-disclosure term and seven days after signing to revoke consent; and 3. after the expiration of the revocation period, the worker and the employer must enter into a second agreement that includes the nondisclosure term and any other terms resolving the harassment claim (Zweig 2020).

36 It is worth mentioning the particular case of those workers, particularly migrant workers, who might have greater difficulty leaving a harmful situation, either because their visas are tied to their employers, who could cancel it at any time, or because they would lose their shelter as well as their job (see ILO 2021c). Naturally, migrant domestic workers who live with their employers are the most vulnerable in that respect. In this regard, Paragraph 7 of the Domestic Workers Recommendation, 2011 (No. 201), suggests: “Members should consider establishing mechanisms to protect domestic workers from abuse, harassment and violence, such as: (a) establishing accessible complaint mechanisms for domestic workers to report cases of abuse, harassment and violence; (b) ensuring that all complaints of abuse, harassment and violence are investigated, and prosecuted, as appropriate; and (c) establishing programmes for the relocation from the household and rehabilitation of domestic workers subjected to abuse, harassment and violence, including the provision of temporary accommodation and health care”.

37 The importance of adequate remedies has been stressed regularly by the CEACR, including the need to grant reinstatement where appropriate; see ILO 2012; 1996. For instance, the CEACR considers that in the “context of protection against victimization, where someone has been dismissed due to raising a complaint, reinstatement is normally the most appropriate remedy” (ILO 2017a, para. 328).

38 For more information, see: Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada, “Boards/Commissions”.