Article 9(b)–(c) of Convention No. 190 acknowledges that violence and harassment, including gender-based violence and harassment, and its associated psychosocial risks, are not only an issue of discrimination and inequity, but also a risk of impaired health.

Article 9

Each Member shall adopt laws and regulations requiring employers to take appropriate steps commensurate with their degree of control to prevent violence and harassment in the world of work, including gender-based violence and harassment, and in particular, so far as is reasonably practicable, to: …

b. take into account violence and harassment and associated psychosocial risks in the management of occupational safety and health;

c. identify hazards and assess the risks of violence and harassment, with the participation of workers and their representatives, and take measures to prevent and control them;

Over the past decades, a number of ILO OSH instruments have been set out to protect workers’ safety and health. These standards include the:

- Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 155) and Recommendation (No. 164), 1981;

- Protocol of 2002 to the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981;

- Occupational Health Services Convention (No. 161) and Recommendation (No. 171), 1985;

- List of Occupational Diseases Recommendation, 2002 (No. 194); and

- Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 187) and Recommendation (No. 197), 2006.

Even if these instruments do not specifically address violence and harassment, such conduct has always been considered as an obvious health risk (ILO 2020d). Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 now make it clear that violence and harassment – including gender-based violence and harassment should be addressed through OSH management. Article 12 of Convention No. 190 specifies that “extending or adapting existing occupational safety and health measures to cover violence and harassment and developing specific measures where necessary” is one of the methods of applying the provisions of the Convention. 29 In a number of countries, OSH legislation already addresses employers’ duty to assess the various safety and health risks associated with their workplace in order to identify, reduce, and whenever possible, prevent them. Although management is responsible for controlling risks, workers have a critical role to play in helping to identify and assess workplace hazards.

Many factors contribute to violence and harassment at work, including psychosocial hazards and occupational stress (ILO 2020h). This being the case, Paragraph 8 of Recommendation No. 206 recommends:

The workplace risk assessment … should take into account factors that increase the likelihood of violence and harassment, including psychosocial hazards and risks. Particular attention should be paid hazards and risks that:

- arise from working conditions and arrangements, work organization and human resource management, as appropriate;

- involve third parties such as clients, customers, service providers, users, patients and members of the public; and

- arise from discrimination, abuse of power relations, and gender, cultural and social norms that support violence and harassment. 30

Psychosocial risks can be defined as those aspects of work design, organization, and management, along with their social and environmental contexts, that have the potential to cause harm. Psychosocial risks that cause occupational stress can also increase the risk of violence and harassment at work. Although violence and harassment can be induced by a number of individual, social and organizational factors, research shows that, for instance, bullying is likely to prevail in stressful working environments where workers are exposed to high levels of interpersonal conflict and noxious leadership styles (Johan Hauge, Skogstad, and Einarsen 2007). Other studies also show a vicious circle of psychosocial risks leading to harassment, which then leads back to psychosocial risks (ILO 2020d). Psychosocial risks vary between sectors, workplaces, groups of workers and occupations. They may include third-party violence and harassment, as well as domestic violence, when relevant. Some of the key and interrelated psychosocial hazards that could lead to violence and harassment, or that are in and of themselves expressions of harassment, may include:

- job content and control;

- workload and work pace;

- working time;

- physical working environment;

- organizational culture and function;

- leadership style;

- interpersonal relationships at work; and

- “normalization” of violence and harassment (ILO 2020d).

Furthermore, discrimination, cultural and language differences, and other vulnerabilities usually interact and intersect with psychosocial risks, thus having an impact on violence and harassment in the world of work. For these reasons, Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 call for workplace risk assessment and management to take into account all of the factors that may increase the likelihood of violence and harassment.

After identifying all hazards and assessing the associated risks, the next step is to adopt appropriate measures to prevent or control such risks, in order to minimize their effects and to prevent similar occurrences in the future.

The identification of hazards and the assessment of risks of violence and harassment can also constitute a channel to address concerns that may be specific to persons with disabilities and other individuals or groups in vulnerable situations. Examples of measures to prevent and control risks may vary and depend upon the nature of the workplace and workforce, as well as on the specific sector where employers operate. These measures could include:

- establishing or updating facility access controls;

- installing security cameras;

- reviewing job descriptions to ensure that duties and responsibilities for workplace safety and security are defined clearly; and

- establishing response protocols in the event of workplace violence and harassment.

Box 21. Violence and harassment as a safety and health issue to be included under OSH regulations

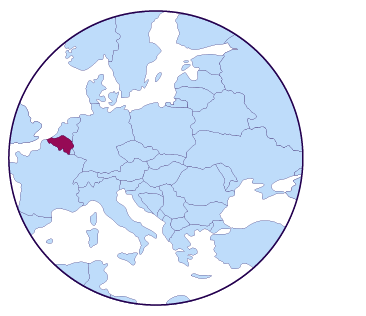

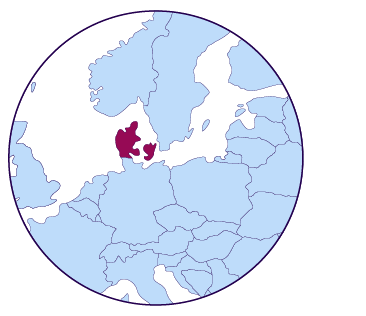

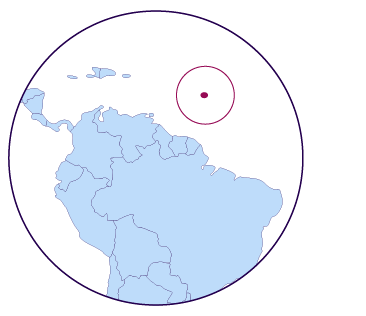

Recently, an increasing number of countries have included specific reference to violence and harassment and its associated psychosocial risks in the management of OSH, including within the scope of workers’ compensation legislation.

29 This is of particular importance for workers in the informal economy. While OSH regulations contribute to protecting workers from OSH risks in the formal economy, those in the informal economy – which in some countries may represent the majority of workers – are often not covered by regulations related to working conditions or OSH due to the fact that the enterprises they work in may be unregulated or unregistered and may not be reached by labour inspection systems. The millions of workers operating in the informal economy may thus face increased vulnerability to violence and harassment, as well as difficulty seeking help or treatment following an incident, especially in the absence of social protection. There is, therefore, a need to continue to promote and strengthen OSH in informal workplaces through training, awareness and targeted programmes. See ILO 2018e.

30 In 2016, the Meeting of Experts on Violence against Women and Men in the World of Work also identified a number of factors that increased the risk of violence and harassment, such as: a) working in contact with the public; b) working with people in distress; c) working with objects of value; d) working in situations that are not or not properly covered or protected by labour law and social protection; e) working in resource-constrained settings (inadequately equipped facilities or insufficient staffing can lead to long waits and frustration); f) unsocial working hours (for instance, evening and night work); g) working alone or in relative isolation or in remote locations; h) working in intimate spaces and private homes; i) the power to deny services, which increases the risk of violence and harassment from third parties seeking those services; j) working in conflict zones, especially providing public and emergency services; and k) high rates of unemployment (ILO 2016b, para. 9).

31 Supreme Decree N° 014-2019-MIMP: The new regulations also require employers to adopt anti-harassment policies and investigation procedures, provide anti-harassment training, and carry out annual sexual harassment risk assessments.