Under Convention No. 190, ratifying countries are required to establish or strengthen monitoring mechanisms to monitor and enforce compliance in relation to legislation regarding violence and harassment (Arts 4(2)(d) and 10(a)) and to ensure effective means of inspection and investigation, including through labour inspectorates and other competent bodies (Art. 4(2)(h)).

Labour inspection is a vital public function that lies at the core of promoting and enforcing decent working conditions and respect for fundamental principles and rights at work. Inspection is instrumental in the protection of labour rights and the promotion of safe and secure working environments for all workers (ILO 2020k). The ILO Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81), and its 1995 Protocol define the functions and powers of labour inspectors, including supervision, injunction and sanctioning powers. 39 According to Article 3 of Convention No. 81, the functions of the system of labour inspection shall be:

- to secure the enforcement of the legal provisions relating to conditions of work and the protection of workers while engaged in their work … ;

- to supply technical information and advice to employers and workers concerning the most effective means of complying with the legal provisions;

- to bring to the notice of the competent authority defects or abuses not specifically covered by existing legal provisions.

In addition, Article 12 of Convention No. 81 states:

Labour inspectors provided with proper credentials shall be empowered:

- to enter freely and without previous notice at any hour of the day or night any workplace liable to inspection;

- to enter by day any premises which they may have reasonable cause to believe to be liable to inspection; and

- to carry out any examination, test or enquiry which they may consider necessary in order to satisfy themselves that the legal provisions are being strictly observed. 40

Article 13(1) further provides that “labour inspectors shall be empowered to take steps with a view to remedying defects observed in plant, layout or working methods which they may have reasonable cause to believe constitute a threat to the health or safety of the workers”. In addition:

In order to enable inspectors to take such steps they shall be empowered, subject to any right of appeal to a judicial or administrative authority which may be provided by law, to make or to have made orders requiring

- such alterations to the installation or plant, to be carried out within a specified time limit, as may be necessary to secure compliance with the legal provisions relating to the health or safety of the workers; or

- measures with immediate executory force in the event of imminent danger to the health or safety of the workers (Art. 13(2)). 41

Along with labour inspectorates, other national bodies may be in charge of monitoring legislation related to violence and harassment in the world of work. For instance, many countries have an independent national body in charge of monitoring and implementing human rights and anti-discrimination legislation; others have bodies that focus on specific groups, such as women (ILO 2017a).

Convention No. 190 provides that ratifying States should “ensure that labour inspectorates and other relevant authorities, as appropriate, are empowered to deal with violence and harassment in the world of work, including by issuing orders requiring measures with immediate executory force, and orders to stop work in cases of an imminent danger to life, health or safety, subject to any right of appeal to a judicial or administrative authority which may be provided by law” (Art. 10(h)). 42 In this regard, Paragraph 21 of Recommendation No. 206 specifies that not only the mandate of national bodies responsible for labour inspection and OSH should cover violence and harassment in the world of work, but also bodies responsible for equality and non-discrimination, including gender equality. Recommendation No. 206 further recommends that labour inspectors and officials of other competent authorities should receive gender-responsive training with a view to identifying and addressing violence and harassment, including psychosocial hazards and risks, gender-based violence and harassment, and discrimination against particular groups of workers (Para. 20).

Box 33. Strengthening monitoring mechanisms

6.2.1. Improving data collection

The development of effective regulations and policies to support a world of work free from violence and harassment requires the collection of timely, comprehensive and reliable data. However, data on violence and harassment are often limited as a result of cultural taboos, shame or fear of speaking up, as well as lack of clarity on what constitutes unacceptable behaviour. Recommendation No. 206 calls Member States to “make efforts to collect and publish statistics on violence and harassment in the world of work disaggregated by sex, form of violence and harassment, and sector of economic activity, including with respect to the groups referred to in Article 6 of the Convention” (Para. 22).

Overall, statistics on work-related violence and harassment are collected through three main categories of sources:

Administrative sources include OSH registries of accidents/illness related to work, police records, compensation records of insurance companies, court records and hospital records. These sources have a limited scope, as they usually capture only cases of physical violence, and are subject to a high-degree of under-reporting when the violent incidents do not lead to severe injuries or fatal outcomes.

Establishment surveys are generally not seen as an adequate data source, as they collect information from employers instead of workers themselves, and employers do not usually have appropriate procedures in place to record cases of violence and harassment.

Household surveys or individual surveys allow for information to be collected directly from the population exposed to or the victims of the violent incidents, and can cover all forms of violence. Therefore, they present some advantages over the two other sources despite the challenges involved in their implementation.

The ILO is working towards the development of international statistical standards on measurement of work-related violence and harassment. The future statistical guidelines will be an essential tool for countries seeking to improve their data collection and will enable them to produce reliable, comparable and policy-relevant statistics.

39 The Labour Inspection (Agriculture) Convention, 1969 (No. 129), similar in content to Convention No. 81, requires ratifying States to establish and maintain a system of labour inspection in agriculture.

40 In relation to examinations, Article 12(1)(c) of Convention No. 81 further specifies that labour inspectors shall be empowered: (i) to interrogate, alone or in the presence of witnesses, the employer or the staff of the undertaking on any matters concerning the application of the legal provisions; (ii) to require the production of any books, registers or other documents the keeping of which is prescribed by national laws or regulations relating to conditions of work, in order to see that they are in conformity with the legal provisions, and to copy such documents or make extracts from them; (iii) to enforce the posting of notices required by the legal provisions; (iv) to take or remove for purposes of analysis samples of materials and substances used or handled, subject to the employer or his representative being notified of any samples or substances taken or removed for such purpose.

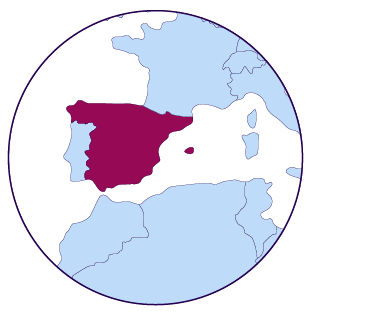

41 With respect to domestic work, labour inspectors are often not allowed in private households to inspect cases of abuse (ILO 2016e). Article 17 of Convention No. 189 does state, however, that Members “shall develop and implement measures for labour inspection, enforcement and penalties with due regard for the special characteristics of domestic work, in accordance with national laws and regulations” and that “such measures shall specify the conditions under which access to household premises may be granted”. Some countries grant permission to labour inspectors to enter private households with judicial authorization, while others have enhanced cooperation with the judiciary with regard to legal presumptions, indicators of abuse, authorization of inspection visits, and urgent judicial procedures for gaining access to the household. For instance, in Spain, Act No. 36/2011 of 10 October 2011 (the Labour Courts Regulatory Act) provides that the General Inspectorate of Labour and Social Security may request judicial authorization to inspect home premises, even where the owner objects or is likely to object, provided that the inspection is related to potential administrative proceedings before the social courts or is intended to enable any other inspection or monitoring related to fundamental rights or freedoms. In Finland, section 9 of the Act on Occupational Safety and Health Enforcement and Cooperation on Occupational Safety and Health at Workplaces (Act No. 44/2006) states that an inspection may be carried out within the sphere of domiciliary peace (privacy), under the adequate authorization procedures, if there is reasonable cause to suspect that the work performed on the premises or the working conditions pose a threat to an employee’s life or health.

42 The Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81) and its 1995 Protocol define the powers of labour inspectors, including supervision and injunction. Enforcement and sanctions should be combined with the provision of information and technical advice, to support employers in the prevention of occupational accidents and diseases.

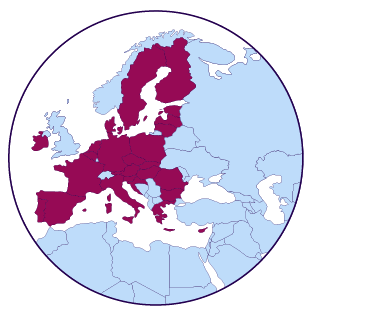

43 For an overview of other EU countries, see European Commission 2016.